Walking through a dense forest, it’s easy to feel humbled by the sheer diversity surrounding you. Every leaf, branch, and bark pattern seems like a secret waiting to be unlocked. I recall countless weekends spiraling into endless walks, notebooks in hand, attempting to decode the silent language inscribed on each tree. For those passionate about ecology, botany, or simply fostering a deeper bond with nature, mastering oak leaf identification feels akin to reading an ancient, intricate map—every detail a route to understanding the forest’s story.

Navigating Nature’s Map: The Art and Science of Oak Leaf Identification

Oak trees, traditionally regarded as emblematic of strength and endurance, exhibit a remarkable array of leaf forms that serve as vital indicators for species recognition. This diversity isn’t merely aesthetic; it encapsulates evolutionary adaptations, climatic responses, and ecological niches. As someone who once struggled with distinguishing a black oak from a northern red oak during a brisk autumn walk, I’ve come to appreciate the depth of information encoded within leaf morphology. Recognizing oak leaves, then, transforms from a simple exercise in taxonomy into a form of ecological reading—like deciphering a forest’s intricate cartography.

The Structural Blueprint of Oak Leaves: Foundation Stones of Identification

At their core, oak leaves are remarkable for their variability. They range from deeply lobed, with sharp indentations, to almost entire, with smooth margins. This heterogeneity reflects both genetic lineage and environmental pressures. For example, the classic lobed leaves of Quercus rubra or Northern Red Oak betray their lineage, while the rounded, almost unlobed leaves of Quercus imbricaria or Shingle Oak present a different visual narrative. The primary features to analyze include leaf shape, margin type, venation pattern, and size—each a piece in the broader puzzle of species identification.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Leaf Margin | Entire, lobed, serrated; varies across species (e.g., lobed in Quercus palustris, serrated in Quercus alba) |

| Blade Shape | Oval, lanceolate, obovate; depends on species and maturity |

| Venation Pattern | Pinnate, palmate; critical for differentiating species within the same genus |

| Leaf Size | Range from 3 to 20 cm; correlates with environmental conditions and species-specific traits |

Key Elements of Oak Leaf Identification: From Recognition to Ecological Reading

Understanding oak leaves isn’t solely about memorizing shape or margin type; it demands an integrated approach that considers context, evolutionary history, and ecological interactions. I remember an early spring, desperately combing through buds and new leaves, trying to match them with published keys and regional flora guides. What struck me during those moments was how leaf traits often reflected the tree’s place in the ecosystem—species distribution, soil preferences, and even historical climatic conditions.

Leaf Morphology as a Reflection of Evolutionary Lineage

Most oak species belong to the genus Quercus, which exhibits a fascinating evolutionary tapestry. Molecular studies reveal that divergence in leaf traits, such as lobing intensity or margin fineness, often aligns with speciation events tied to geographic and climatic shifts. For example, the classic lobed leaves of Quercus robur (English Oak) contrast sharply with the unlobed or mildly lobed leaves of related species adapted to different habitats. Recognizing these patterns can serve as shortcuts—ecological clues guiding a more sophisticated understanding of regional flora.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Historical Evolution | Genetic divergence reflects adaptation to climate, soil, and competition |

| Geographical Distribution | Lobed oaks predominate in temperate regions, with variation correlating with environmental gradients |

| Phenotypic Plasticity | Leaf morphology can vary intra-specifically based on local conditions, adding complexity to identification |

Practical Strategies for Deciphering Oak Leaves in the Field

Though the science might seem daunting at first, I found that empirical, hands-on practice is paramount. Early on, I adopted a simple but effective approach—collecting leaves, photographing them with standardized scales, and comparing them side-by-side with field guides. Over time, I learned to pay close attention to venation patterns: Are the veins pinnate or palmate? Are the lobes symmetrical? Is the margin serrated or smooth? Climate and seasonality also influence leaf shape; I remember how summer leaves often differ from autumn ones—margins may become more serrated with age or stress, adding layers to identification.

Utilizing Botanical Keys and Digital Resources

Modern technology has revolutionized this process. Digital apps, high-resolution image repositories, and AI-powered recognition tools empower amateur and professional botanists alike. I’ve used apps like iNaturalist to confirm species, and I’ve found that cross-referencing images with authoritative botanical keys enhances confidence. Still, growing comfortable with traditional dichotomous keys remains vital—these prepared me for field conditions where digital connectivity might falter.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Field Techniques | Consistent sampling, photographing, and note-taking improve identification accuracy over time |

| Digital Tools | Apps and online databases augment traditional methods, especially for unfamiliar species |

| Community Engagement | Sharing findings in online forums fosters learning and peer validation |

Understanding the Forest Map: Broader Ecological Significance of Oak Identification

Beyond individual identification, recognizing oak leaves contributes to a broader understanding of forest composition, health, and resilience. In my own experience, tracking changes in leaf morphology over seasons and years revealed shifting ecological patterns—be it due to climate change, invasive species, or human disturbance. For instance, the decline or abnormal leaf shapes in certain regions signaled stressors impacting oak populations. Such insights demand a holistic appreciation of leaves not merely as botanical curiosities but as vital indicators of ecosystem vitality.

The Role of Oaks in Forest Ecosystems

Oaks serve as keystone species, supporting myriad forms of wildlife—from insects and birds to mammals. Their leaves influence soil quality through leaf litter dynamics, affecting nutrient cycling. Recognizing leaf differences also helps in identifying subspecies or hybrids, which are crucial for adaptive management strategies. For example, hybrid oaks with variable leaf morphology can complicate identification but also signify evolutionary processes at play.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Ecological Indicators | Leaf diversity reflects genetic variation and adaptive responses within oak populations |

| Conservation Strategies | Accurate identification underpins efforts to protect vulnerable species and manage invasive threats |

| Climatic Insights | Changes in leaf morphology patterns can presage broader climate impacts on forest health |

Addressing Challenges and Limitations in Oak Leaf Identification

As rewarding as mastering oak leaf identification is, several challenges inevitably arise. Variability within species can trigger misclassification, especially when environmental stressors cause atypical leaf forms. Additionally, seasonal changes—bud break in spring, senescence in fall—offer different visual cues, sometimes leading to confusion. My own encounters with hybrid oaks blurred species boundaries, illustrating the importance of integrating multiple traits—such as acorn characteristics or bark texture—into identification efforts.

Hybridization and its Impacts on Identification

The phenomenon of hybridization among oaks complicates the task, as hybrids often display intermediate features. This genetic blending is a natural adaptation but can perplex even seasoned botanists. For instance, the hybrids between Quercus rubra and Quercus velutina can show a mosaic of leaf shapes and margins. Such cases emphasize the importance of a multifaceted approach—combining leaf morphology with other diagnostic features and, when possible, genetic analysis.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Misclassification Risks | Overlap in leaf traits among species and hybrids can lead to errors |

| Strategies to Mitigate | Use multiple traits—acorn shape, bark, growth form—and habitat context for reliable identification |

| Genetic Tools | DNA barcoding offers definitive identification but remains less accessible in fieldwork |

Conclusion: Embracing the Forest’s Hidden Language

Stepping back from the technicalities, recognizing oak leaves as part of a larger, interconnected ecological tapestry feels like decoding an ancient language. My own journey—marked by failures, revelations, and moments of quiet awe—has underscored that every leaf offers a story. Whether interpreting a lobed silhouette or a serrated margin, I see the forest in a new light: as a map of histories, adaptations, and ongoing evolution. To truly master the art of leaf identification is to forge a deeper relationship with the natural world, reading its silent messages with curiosity and respect.

What are the most common oak leaf types I should learn first?

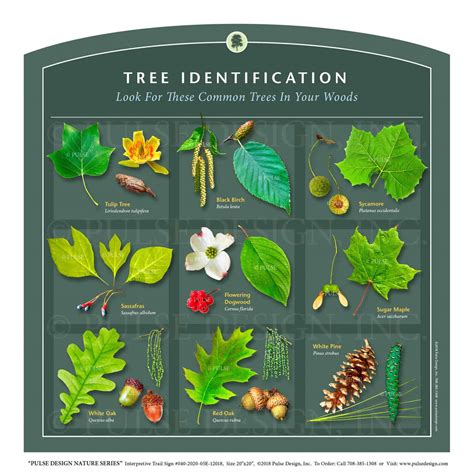

+Starting with the four primary types—entire (smooth margin), lobed, serrated, and pinnately lobed leaves—is best. Focus on familiar regional species like Quercus alba (White Oak), Quercus rubra (Red Oak), Quercus palustris (Pin Oak), and Quercus velutina (Black Oak) to build a solid foundation.

How can digital tools assist in oak leaf identification?

+Apps like iNaturalist and PlantSnap utilize image recognition algorithms trained on extensive botanical databases. They can quickly suggest species based on leaf photos, but should be used in conjunction with physical identification keys for accuracy, especially when encountering hybrids or atypical specimens.

What role does environmental context play in identifying oak leaves?

+Habitat clues—such as soil type, nearby plant communities, and geographic location—are invaluable. For example, certain oaks prefer wet, acidic soils, which narrows down potential species. This ecological backdrop complements leaf morphology, helping to avoid misclassification.